Video of refugee’s life story made available to schools

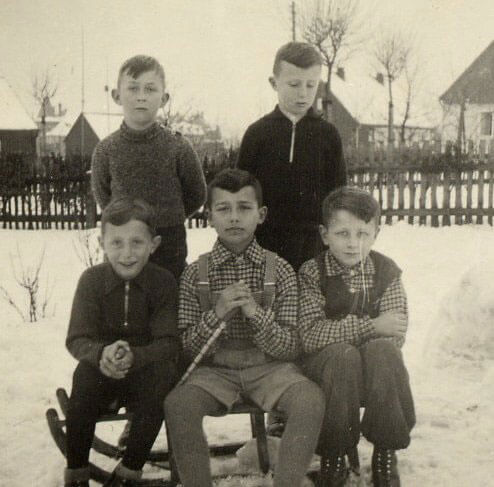

Gathering the Voices has made a video telling the story of German refugee Martin Anson journey to finding a new home in Scotland, with Education Scotland agreeing to promote the video to Scottish schools. Continue Reading Video of refugee’s life story made available to schools